We are not the artifice we present to the world. The version of ourselves that we place on display is, for most of us, not truly reflective of who we are when we are alone. That who we are when alone, that is the person we are most close to actually being. Whether we like being alone or not, that speaks volumes about how well we have nurtured who we are and how well we like who we are. In silence we hear our actual self, the insecurities, fear, concerns, and worries, or the hopes, expectations, plans, and ideally our creative visions. What we hear in our times with silence speaks to who we actually are, stripped of the face we display for others. In that silence of our time away from others we hear, if we choose to listen, the voice within us that tries to quietly guide us to who we can be. That quiet voice needs quiet to be heard, it needs stimulation to grow. Given time to develop, that voice can become louder, loud enough even to be the voice that we hear come from ourselves when we share spaces and time with others.

https://photos.smugmug.com/12-29-19-Canon-F-1N/i-QRGzvQJ/0/64ed0e01/X4/12-29-19%20F-1N%20Portra%20160%20%2810%29-X4.jpg

Silence, and our embrace of it, are prerequisite to our creative drive. Embracing the quietude of a small space, maybe our living rooms, or a large space, maybe at the shore of a still pond, trains us to listen for that creative voice inside. For me, that silent space is solitude in nature, a complete aloneness where silence is not mute but filled with the calls of crickets and frogs, the woodwind-like background of gentle wind caressing tree branches, creaks like a string instrument from those swaying trees, the soft timpani of wind on a quiet lake and the slide and tap like wire brushes on a snare drum when small, wind-driven waves reach shore. Silence is not just being alone with the electric hum of our nervous system. Silence can, and should be, a place where the fullness of solitude reaches through us and shapes us into something new. Silence can help us become more human, become the person we can be, something that exceeds the sum of our parts and experiences.

https://photos.smugmug.com/12-29-19-Canon-F-1N/i-FFjntw9/0/584b20f5/X3/12-29-19%20F-1N%20Portra%20400%20%2830%29-X3.jpg

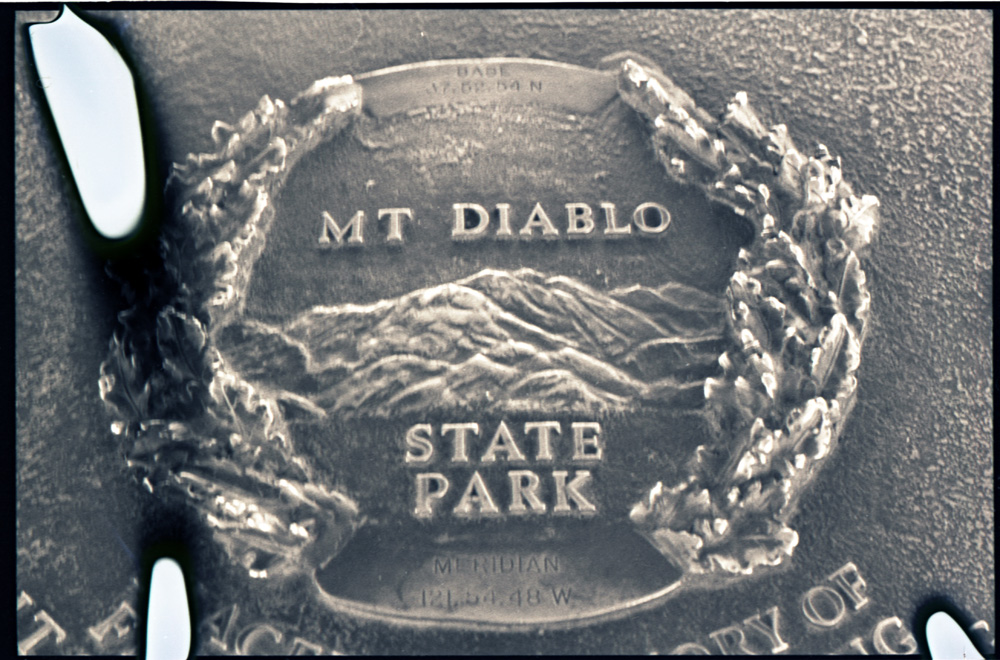

When does a camera become a camera? Is it when the last screw is put into it at the factory? When the first owner takes it in his or her hands and excitedly starts to learn how to use it? Does it not become a camera until it takes its first photo? When it gets its first scratch? Maybe not until the first time someone calls it “my camera.” Does it become a camera at some other time, some moment when the nature of it defies basic definition, allows the object to expand beyond its object-ness, into something more than the sum of the parts, more the function of the design.

https://photos.smugmug.com/12-29-19-Canon-F-1N/i-zhbwnrp/0/3182c448/X3/12-29-19%20F-1N%20Portra%20160%20%2820%29-X3.jpg

There are cameras for which their use is special. There’s a certain click with them, a unique and undefinable attribute, a soul, that makes using them an experience that transcends rote or routine photography. The F-1N is not one of those cameras. It does not drink home-made kombucha and discuss mysticism. It is a Lexus, not an Alpha Romeo; an efficient corporation, not a quirky non-profit; and a river, not an ephemeral stream. The F-1N is all-business, factual, blunt, and when these cameras work correctly they are reliable, take very good pictures, and do exactly what is needed without getting in the photographer’s way. And as I’ve said in many reviews, that’s what a camera should do and that means that the F-1N ticks all the important boxes for me about what makes a good camera. To that end, this camera became a camera when the final drawing was signed, the final specification approved, the final prototype modified the final time, before the first of the production units ever arrived as parts from multiple suppliers to be compiled into a single piece designed to serve a single function.

https://photos.smugmug.com/12-26-19-Canon-F-1N/i-v7mXjCp/0/df8e9726/X3/12-26-19%20F-1N%2050D%20%2811%29-X3.jpg

The engineers and designers who develop cameras, in my mind, create the best product they can based on their understanding of photographers’ needs, or the way in which their marketing department plans to sell the gear. I tend to think that they design something to be the best it can be and then send it out into the world to make its mark. I think that all creativity works in the same way. This includes the creative time and energy we put into ourselves, the time we spend embracing the fullness of silence when we can find it, and the resulting deepness that brings out from within us.

https://photos.smugmug.com/4-25-20-Canon-F-1N/i-KNvPcQv/0/5bf856c1/X3/4-22-20%20Canon%20F-1N%20400H%20%289%29-X3.jpg

What is the nature of creating and creativity? As a creator, as someone who labors to improve his writing and photography, as someone who spent seven years learning to craft the written word, I like to think I have a special insight into this subject. The nature of creativity is repetition and practice infused with mistakes and corrections. Creativity is a spark, sure, an idea that stems at a point in our brains unreachable through even the most concentrated thought, audible only when we learn to listen for it. But that spark is nothing without work, time, and diligence. That creative moment, that point at which an idea commences, dies quickly without support. Creativity unfed by time, effort, and work is like a person unfed and in time that creativity will weaken and die.

https://photos.smugmug.com/12-26-19-Canon-F-1N/i-tG88m6B/0/77d0eecc/X4/12-26-19%20F-1N%2050D%20%2823%29-X4.jpg

You’ve likely heard the cliché ‘the creative process.’ And it’s a cliché because it is true, because creativity is never a destination, never a goal that can be achieved. Forever it will be a process that will lead you wherever you’d like to go with it, for good or ill. The tools of creation are not enough. Creation is an act that uses tools. Shelves full of cameras that collect dust will never advance a creative effort without use. Find a reliable camera. Find a few good lenses. Find a place in which you can embrace a bountiful silence. Find in yourself the voice you can release, the voice that has something to say. It is there waiting to be heard, waiting to be fed, waiting to guide you, and waiting for that moment when you hear it, lift your camera to your eyes, and create something of value.

https://photos.smugmug.com/12-26-19-Canon-F-1N/i-KTr49cm/0/02d67d31/X3/12-26-19%20F-1N%20400H%20%2825%29-X3.jpg

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

%20B-X2.jpg)

-L.jpg)

-L.jpg)

-L.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-X2.jpg)

-L.jpg)