10- For digital cameras, shoot at the lowest sensitivity or your camera's sensor's native sensitivity.

Manufacturers boast of their camera models' high-ISO performance. And in general high-ISO performance has improved dramatically in recent year. However, high-ISO settings don't change how your sensor functions; high-ISO settings take vastly underexposed images and extrapolate image data to create the resulting images. For your model camera, check out the high-ISO test results available on camera testing websites (easily found with a Google Internet search) and you'll see that as sensitivity numbers increase, image clarity decreases.

To obtain the sharpest images your sensor can provide, shoot at the native ISO. For cameras with sensors having a native ISO of 100 but the ability to shoot to lower ISOs, 100 ISO still presents the best option for image sharpness. Some cameras have a native sensor ISO of 200. So the first step is to learn your camera's native ISO. You can find this out in your instruction manual or, in all likelihood, by checking the camera's ISO settings and setting your camera to the lowest ISO available without extended range options.

Also know your enlargement or final image size. Smaller images can contain more high-ISO noise without image quality loss.

Shooting at the native ISO reduces noise and fuzzyness. Shooting a stop or two above the native ISO typically deliver acceptable results (in fact, a professional photographer my company hired shoots all his work at ISO 400, even though I think that's not the best practice for professionals.) That said, older cameras, especially, are less capable of delivering high-ISO performance than newer ones. And as ISO settings increase the image's maximum print or viewing size decreases. Your maximum usable ISO will be meaningfully different if you're shooting for a 5X7 print versus a 16X20 print.

9- Recognize the difference between sharpness and acutance,

Sharpness refers to the actual image detail level. Acutance refers to the contrast differences and gradations between adjoining tonal areas (on a pixel-by-pixel or grain-by-grain basis.) The graphic below shows the difference between an acute and gradual tonal shift. Acutance represents contrast between two adjoining small areas within an image.

An image can have good acutance without good sharpness. For instance, in the sunset shot below the pine tree needles have good sharpness and good acutance. The mountain ridgeline in the distance has good acutance by not good sharpness (hence the black shadow line along the top.)

Acutance improvement can help correct sharpness loss to a point. Only to a point.

8- Know when to stop sharpening.

You've probably seen those photos with a halo around different tonal ranges. Here's a pretty egregious example. The halo around the sky, extreme contrast, and unnaturally sharp shadows indicate acutance over-use (in Photoshop, this is called Sharpness, but it really isn't sharpness.)

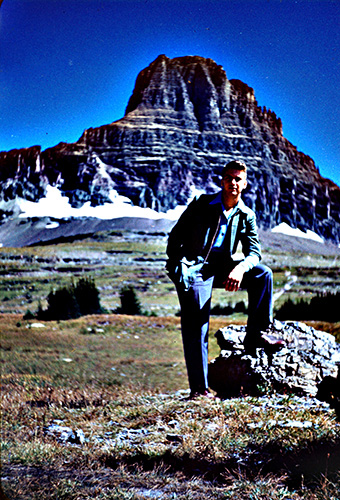

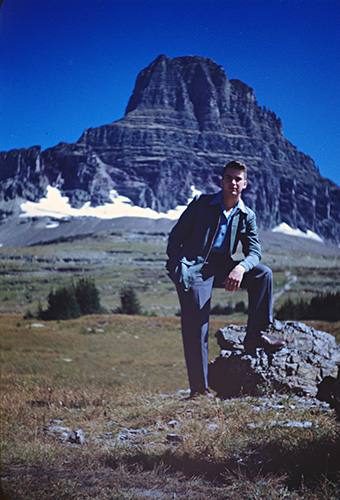

Here's an example of an image with good sharpness that received an appropriate and small amount of acutance enhancement. The image tones are appropriate (the halo effect here is from the slide film, not post-processing), shadows have depth, and the end result is a deeper, more natural-looking image.

8- For film cameras, use the lowest-grain film available.

Interestingly, ISO 400 film can produce some of the sharpest film images in terms of image acutance. However, low-ISO films such as Ilford's PanF 50 can be enlarged more and show less image grain. Low-ISO films can attain greater image sharpness but sacrifice some image acutance.

7- Use a sharp lens.

Do not read that as 'Use and EXPENSIVE lens.' Many very sharp lenses exist other than Pentax, Zeiss, and Voigtlander. Many of these lenses are older lenses and can focus at sharpness ratings modern affordable lenses can't even comprehend. For instance, the Pentax SMC-M 50mm 1:2 can resolve, at it's sharpest aperture at the image center, at up to 160 lines per millimeter. That's sharper than the human eye can see by a fairly significant margin.

Modern lens liner per millimeter ratings can be extremely hard to find, but film and sensor line per millimeter ratings are not. Film manufacturers typically publish their emulsions' sharpness ratings because it helps photographers. So for your selected film, check out the manufacturer's technical sheet, which ought to be on their website.

For your digital camera, divide the sensor height (or width) in millimeters by the number of pixels in the image width. That's how many pixel lines exist per millimeter. For instance, my Pentax K-3 has a 24 megapixel sensor that is 23.5mm wide and produces 6,016-pixel-wide images for 298 pixel rows per millimeter. My K-7 has a rating of around 198 pixel rows per millimeter. If possible, try to pair your lens and sensor as closely as possible.

6- Shoot at the sharpest aperture.

Many good reasons exist to shoot at wide apertures and this item is in no way intended to discount them. For the purpose of simply obtaining the sharpest image, find out your lens' sharpest aperture (typically available on camera technical review blogs and pages across the Internet). Use that aperture when sharpness is paramount.

5- Know the aperture to which your lens is diffraction-limited.

Lenses after a certain aperture begin to exhibit diffraction softness. The same review that will tell you about your lens' sharpness ought to share the diffraction limit, too. When possible, avoid shooting beyond that point. For instance, I rarely shoot smaller than f16 due to diffraction.

Compounding this, cameras with higher-megapixel sensors reduce a lens' diffraction limit. For instance, on my K-7 with it's 14.6 MP sensor I can shoot my 50mm SMC-M 1:1.4 to f16 without diffraction-related image loss. On my K-3 with it's 24 MP sensor, I'm limited to f11 before diffraction softening occurs. I have read that on the Nikon D800 with it's 36-mp sensor that diffraction begins on many lenses at f8 -- an aperture that ought to be extremely sharp on most if not all lenses.

4- Learn to use manual focus.

Manufacturers make a lot of noise about how great their autofocus systems are. For some purposes, such as shooting a motorcross race, autofocus is very useful. However, when you can, you should focus manually as it trains your eye to see sharp detail and soon your eye will be able to pick out details better than the autofocus system.

Why? Because your eye sees the world more clearly. AF systems rely on light points being in focus but those points are larger than your eye can focus on. Delving a little into the technical, a human eye with 20/20 vision can discern an object with a spatial range of one arc minute (1/60th of a degree.) That's a very fine level of detail that exceeds autofocus capabilities. Also, relying on your eyes will help improve your photographic skills in many other ways (but that's a top ten list for 2015 -- I already have 52 lists in development for 2014.)

3- Don't use filters (except for black and white film).

Filters reduce image quality, especially cheap filters. They can reduce image quality significantly, in fact, and can soften images as much as a two-stop increase in ISO (on digital cameras.) I know the argument -- cheap filters break instead of your lens if you drop it. Well, not really. Force will travel through the small filter ring and right into the lens. Breaking filter glass can scratch lens element glass. A bent filter ring can be very hard to get off and the removal process can damage the lens.

So how do you prevent your lens from breaking in a fall? Refer to the next item.

2- Get a lens hood.

Lens hoods block extraneous light from entering the image, eliminating flare and reducing diffraction and other image quality issues. This improves image quality in general and can improve image sharpness by eliminating interfering light.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons user Geni, used under a Creative Commons Attribution and Share Alike license. Use of this image does not constitute the author's agreement with this image's use or this post's content. Here's the link.

As an added bonus, if you drop you lens the lens hood acts like the crumple zone in your car and absorbs the impact. Metal hoods work the best because they bent and absorb all the force. Plastic hoods are okay but can crack or shatter and only partially break a fall. Home-made hoods from cut radiator hose are the best because they're indestructible and also absorb all of the impact force.

1- Stop worrying about sharpness and enjoy taking the image.

Enjoy your time photographing things. You'll take better images in general and specifically sharper images. Your eye will be drawn to focus on something you enjoy and that part of your image will be very sharp.

Top Ten Tuesday will return in a week with Ten Ways to Plan a Photo Shoot.

No comments:

Post a Comment